Recommendations

By: Team Indianapolis, May 2015

The state of transparent police accountability reporting varies widely across the country today. This is a good thing. A diverse group of departments across size, geographic region and situation are all attempting a variety of strategies and tactics for promoting better community relationships by being transparent around what they are doing well and where there is room for improvement.

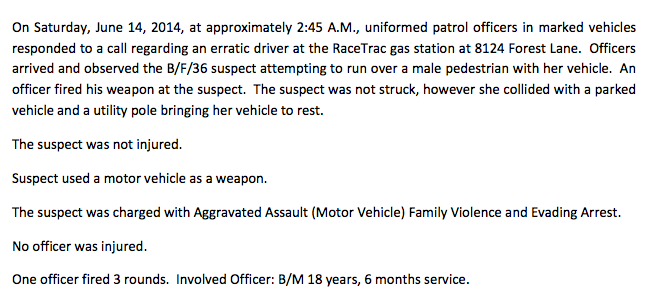

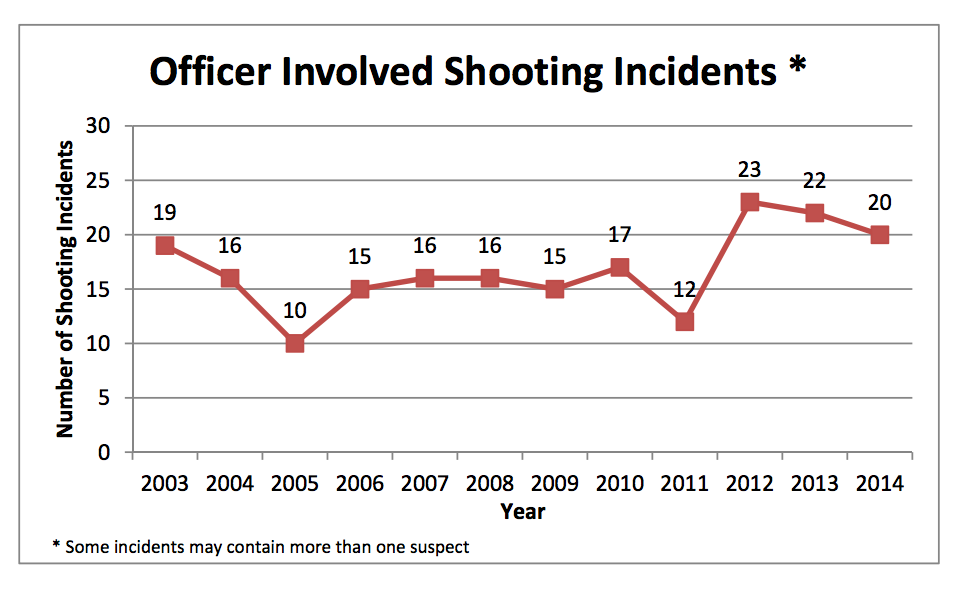

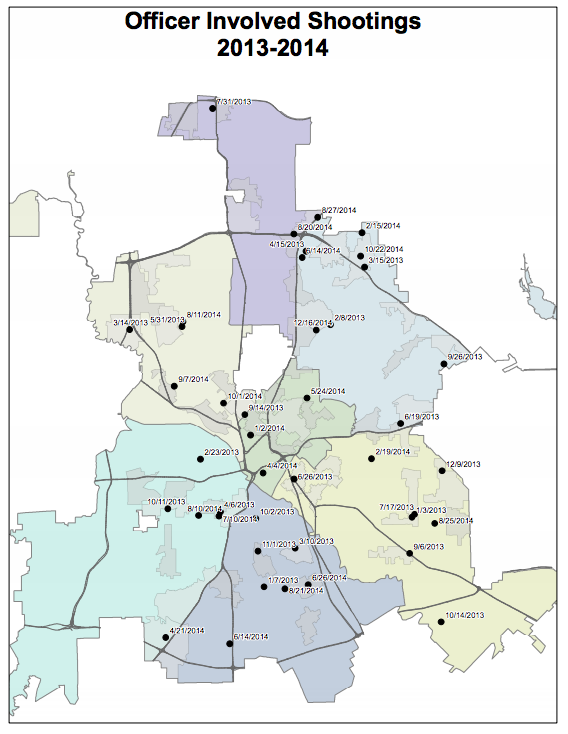

We built our Police Open Data Census to surface as many of these early adopters as possible. We’ve begun to assemble a cross section of these departments and have seen first hand where the state of the art stands. Datasets vary from full annual accountability reports from the the Magnolia, Texas police department (13 officers, population 1,547) to the incredibly detailed incident decision letters issued by The Office of the Denver District Attorney every time a member of the Denver Police Department (1,470 officers, population 607,051) uses force in the line of duty. Looking at the cross section of this information we’ve prepared the following recommendations with the hope of offering departments interested in starting or augmenting open accountability programs with the best practices currently in use and seeing where similar departments stand. We also hope that the Census and these recommendations will serve as a valuable tool for interested residents to know what practices to advocate their local departments adopt and serve as evidence of the feasibility and impact these programs can have.

These recommendations should be considered “living” and, as such, any comments or alterations are more than welcome at Indy@CodeForAmerica.org.

We’ll begin the recommendations with the six cross-cutting vectors we evaluated each dataset in the Census on:

1. Freely Available Online Data:

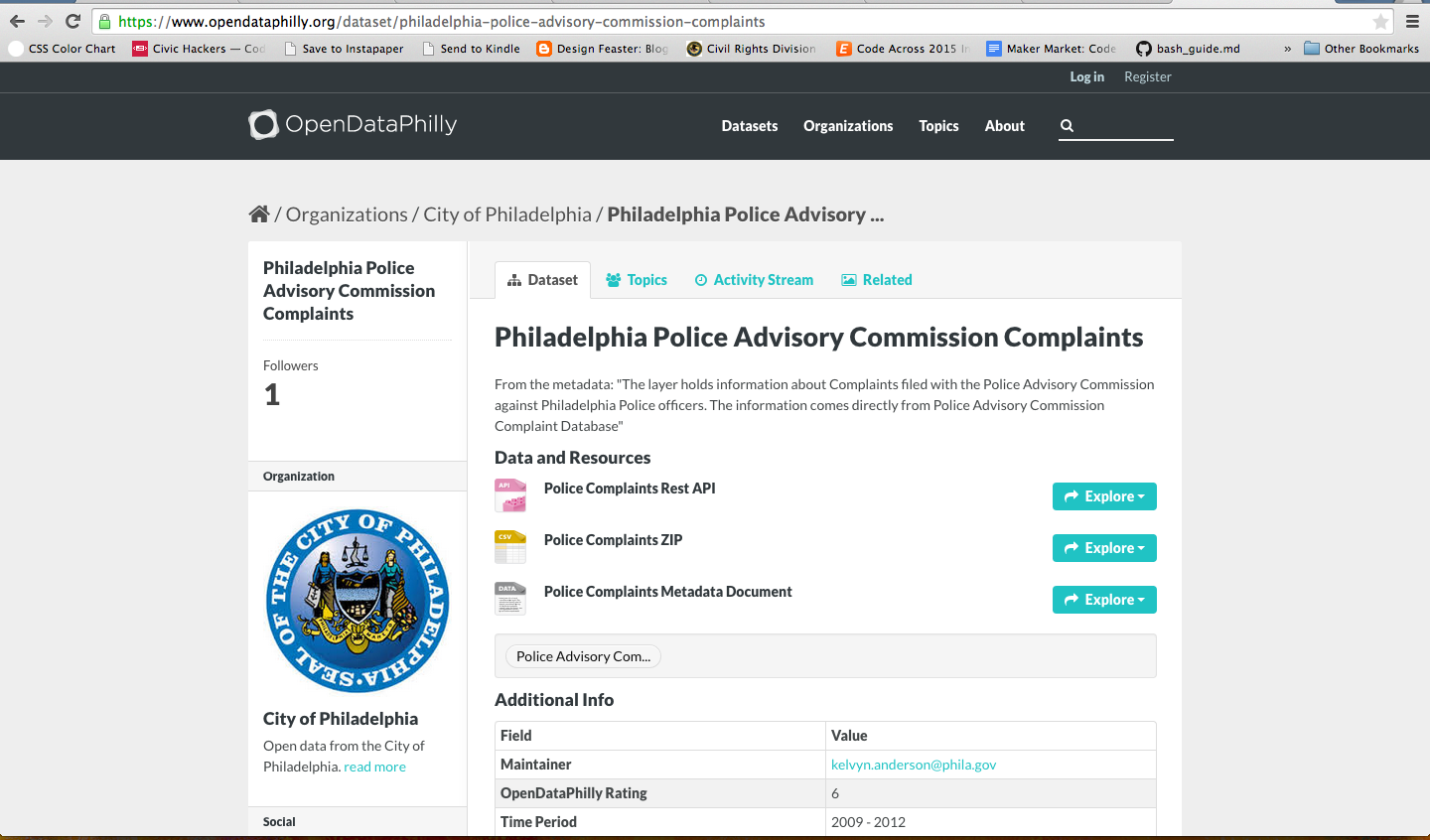

Any information that departments release should be available to the general public on an easily accessible and discoverable website.

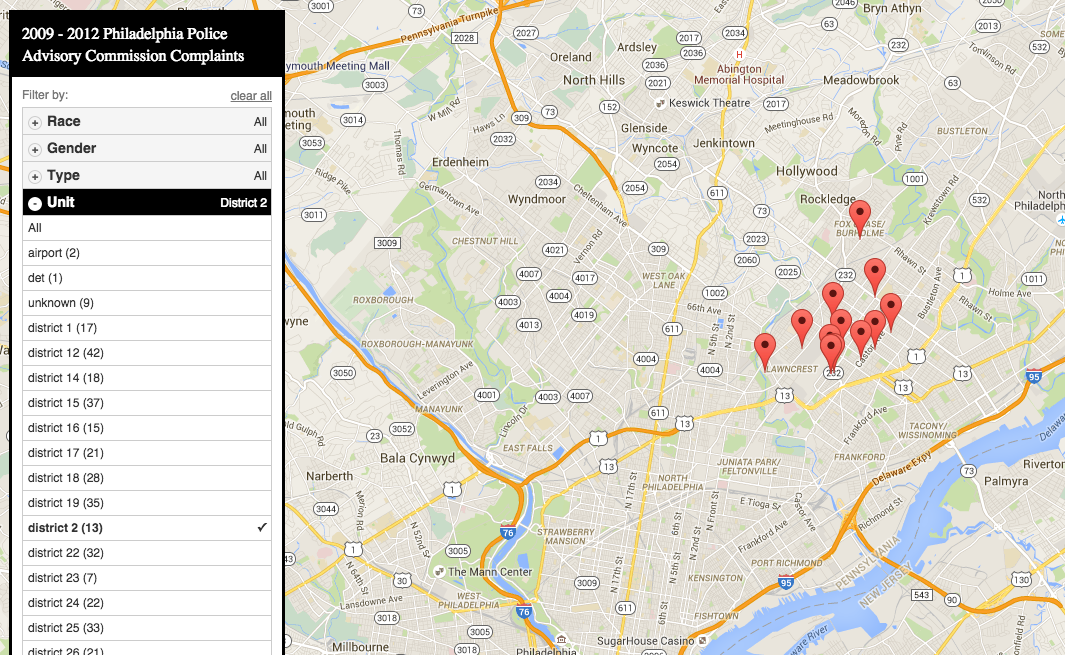

Ideally, departments should prominently feature links to this data on their websites and should routinely evaluate how accessible the data is from the perspective of external users. Consider that not all external users will necessarily know what policing specific terms (like “Internal Affairs”, “CALEA”, or “Office of Professional Standards”) mean or that the data they are looking for will be listed under those terms. Many cities have adopted open data portals from vendors like Socrata or Esri and several departments make their data available through them. If your department is releasing data like this, ensure again that users can easily find your data through both the portal and from your department’s website.

2. Machine Readable Data:

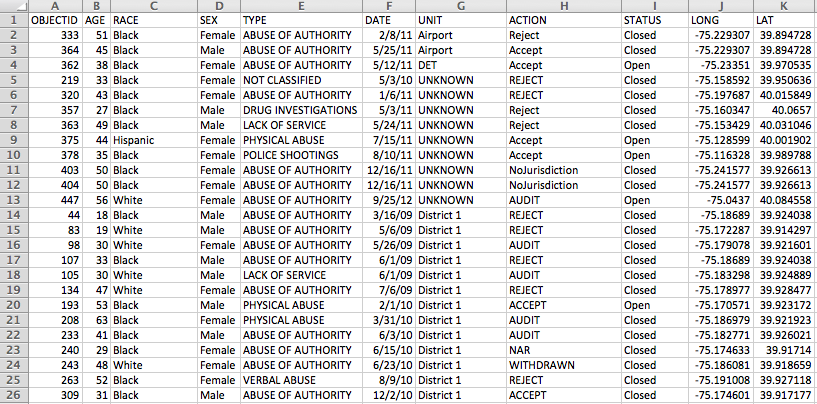

As much as possible, any data released should be provided in a machine readable format (.csv, .json, .xml, etc.) in addition to any reports or web pages made for the general public.

Data made available in PDFs and HTML pages are not generally considered machine readable. While technology exists to extract data from both, departments should make machine readable data in one of the other formats listed. Code for America advocates for machine readability in open data to “drive internal efficiency, spark community engagement, and fuel a civic tech ecosystem” by allowing the data to be used in conjunction with other datasets, applications or wider uses. Departments have found that by releasing data in machine readable formats, the wider community, in addition to those inside the department, can put the information to productive uses that were not initially considered. It will also greatly aid efforts like those by the Police Foundation and the Sunlight Foundation to provide for better national police accountability data gathering.

Given the sensitivity of the police accountability data, departments should avoid only releasing machine readable data. It’s important that a general audience website or report summarizing and contextualizing the released information be made available first. Additionally, users of civic Open Data platforms should ensure that they completely fill out the metadata pages so consumers fully understand what they’re receiving. Preferably, the machine readable data should be easily accessed from similar paths as discussed above.

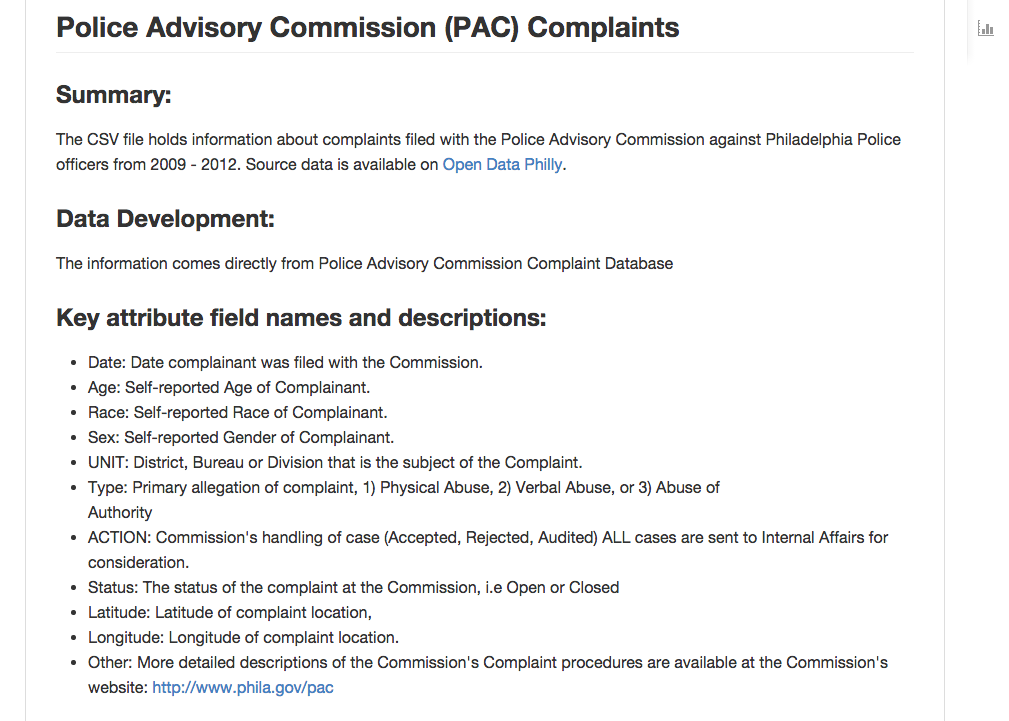

3. Provide Context:

Releasing sensitive data should never be done without some attempt to contextualize and explain the information

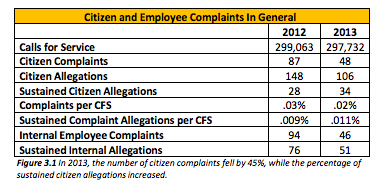

The general public should be brought up to the department’s level of understanding around what the numbers in the data mean, any trends the department is aware of and what the required context is for correctly interpreting the provided data. Particularly useful to provide is some measure of the number of total police interactions with the public during the timeline of the data. Often this takes the form of the number of calls for service and the number of arrests. Providing this information can contextualize information like Use of Force incidents or Pursuits to the actual level of policing activity a department engages in. If a department provides data at a more granular level than annually, it can also help contextualize seasonal changes in policing activity that may otherwise appear as significant swings in incident frequency.

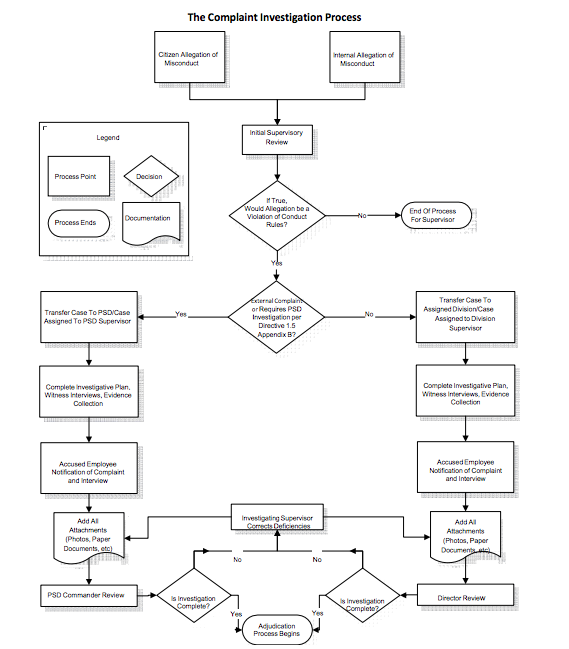

In addition to this contextual data, it is also important to provide explanations on what each field in a dataset represents. A common example is helping the general public to understand the typical dispositions of the police complaint process e.g. Sustained, Not Sustained, Exonerated, Unfounded. Again it’s valuable to approach this process from the perspective of the general public who may not be familiar with police-specific terminology and acronyms.

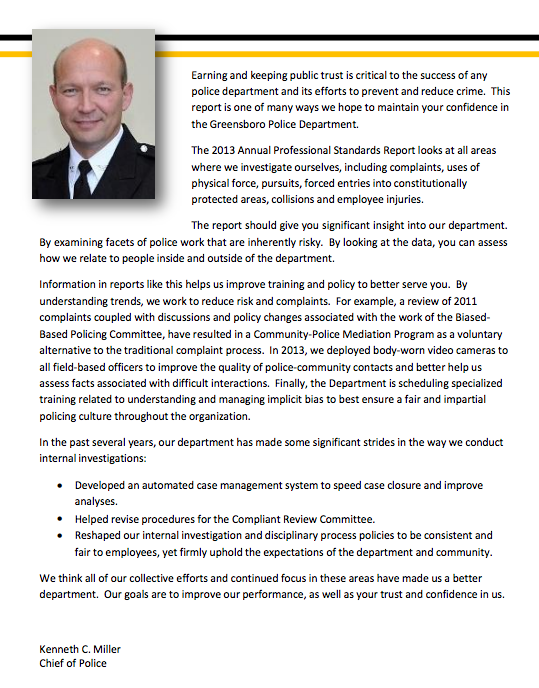

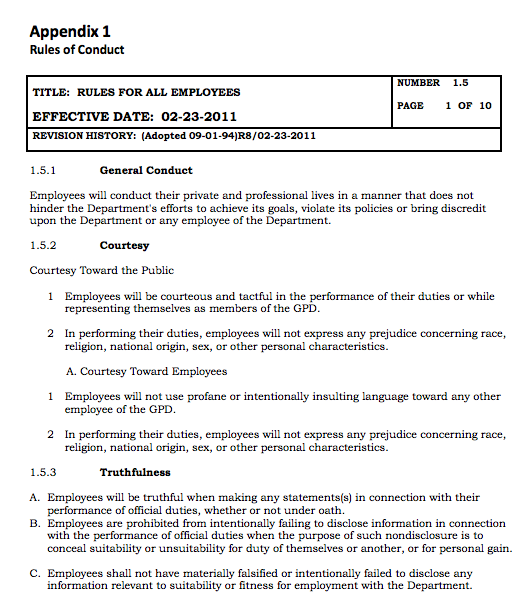

Two other valuable things a department can provide alongside a dataset include a short introduction from a high ranking member of the department introducing the data, explaining why the department is interested in releasing this information, the steps the department is taking based on the information included, and the full text of any relevant departmental policy or general orders.

4. Bulk Availability:

The released data should be available in as few downloads as makes sense.

If a department provides incident level data it’s good to make those available in a single bulk download/page/report in addition to providing them separately. This is most relevant for machine readable data where it should be assumed that consumers of the data want all of it in as little additional work as possible. Most Open Data platforms will provide this functionality by default.

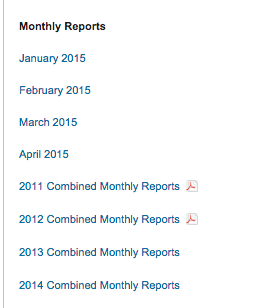

5. Up-to-Date Data:

Data should be released at sensible and predictable intervals.

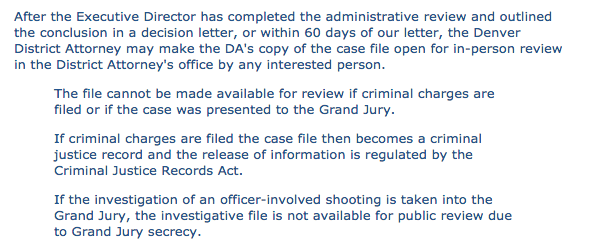

Many departments in the Census release data annually. Others release incident level data as soon as they are legally permitted to do so. We understand that the work involved in collecting, collating and cleaning information means that annual releases are the the only sensible option for many departments. It is our hope that as departments move toward standardized software solutions for Professional Standards (e.g. CI Technologies’ IAPro), the work involved in data release can be automated to the point that it can be done far more often. If a department is committed to set interval reports (e.g. annual, monthly), information should be provided around the expected release date of the next report and be kept up to date itself. If a department releases information on an incident by incident basis, the process that dictates when information can be released should appear alongside the data. If possible, some measure of the amount of data “in the pipe” should be provided as well.

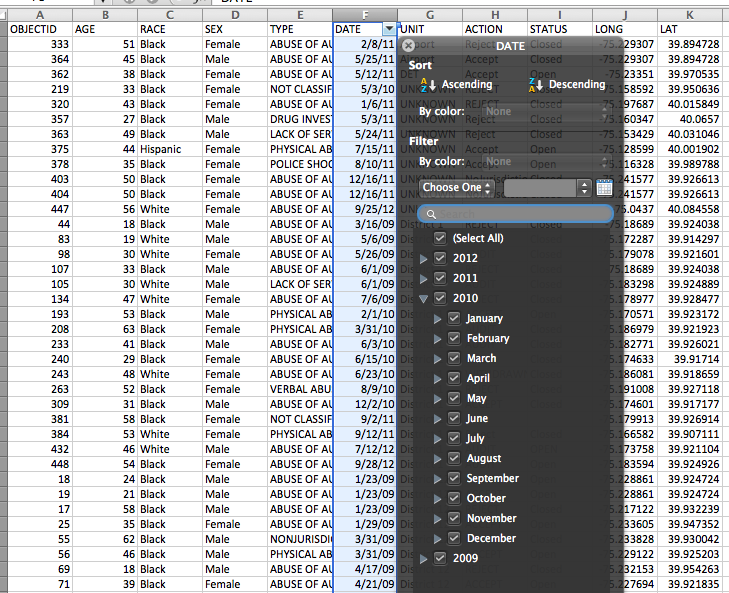

6. Incident Level Data:

If possible, data should be released at the incident level.

Many departments who release data annually condense and summarize their data sets. While this provides a good overall depiction of the state of the department, it removes a significant amount of value that can be gleaned from examining incidents at a more granular level. For instance, releasing a summary count table of “Reasons a Pursuit was Initiated” and a summary count table of “Reasons a Pursuit was Terminated” gives a good indication of general trends in what pursuits in a city look like, but prevents deeper analysis of the connection between those characteristics. Given the sensitivity of police accountability data, incident level data has to be handled with deliberate care to avoid publishing information that should not be public, but doing so strongly demonstrates a dedication to transparency. As with several other of the above concerns, there should not an “either or” decision between incident level data and summarized data. Ideally, both should be provided for “wide” and “deep” analysis and public understanding.