Executive Summary

We've been working with the City of West Sacramento and the Sacramento Area Council of Governments (SACOG) to explore and address challenges in the local food ecosystem.

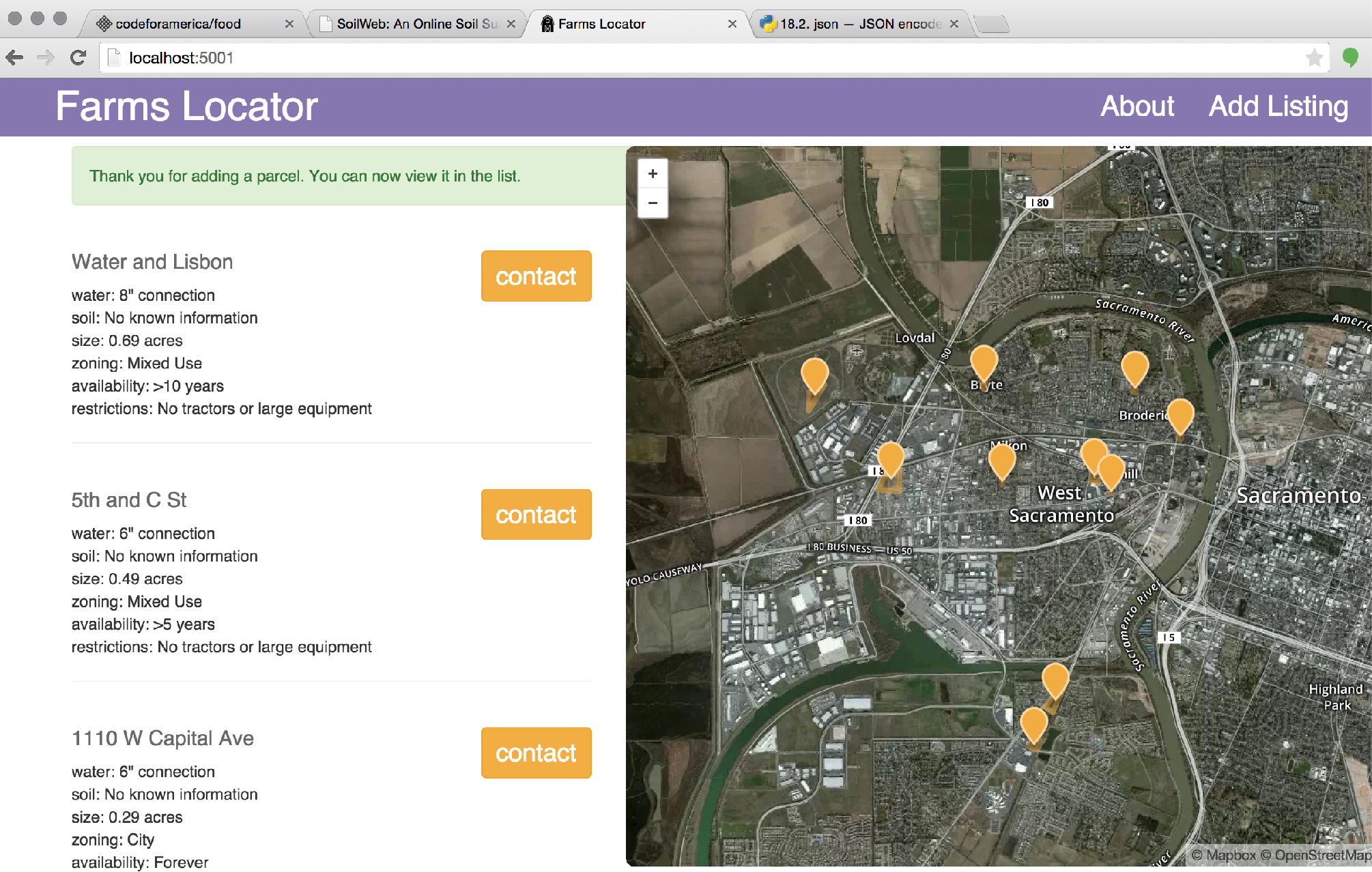

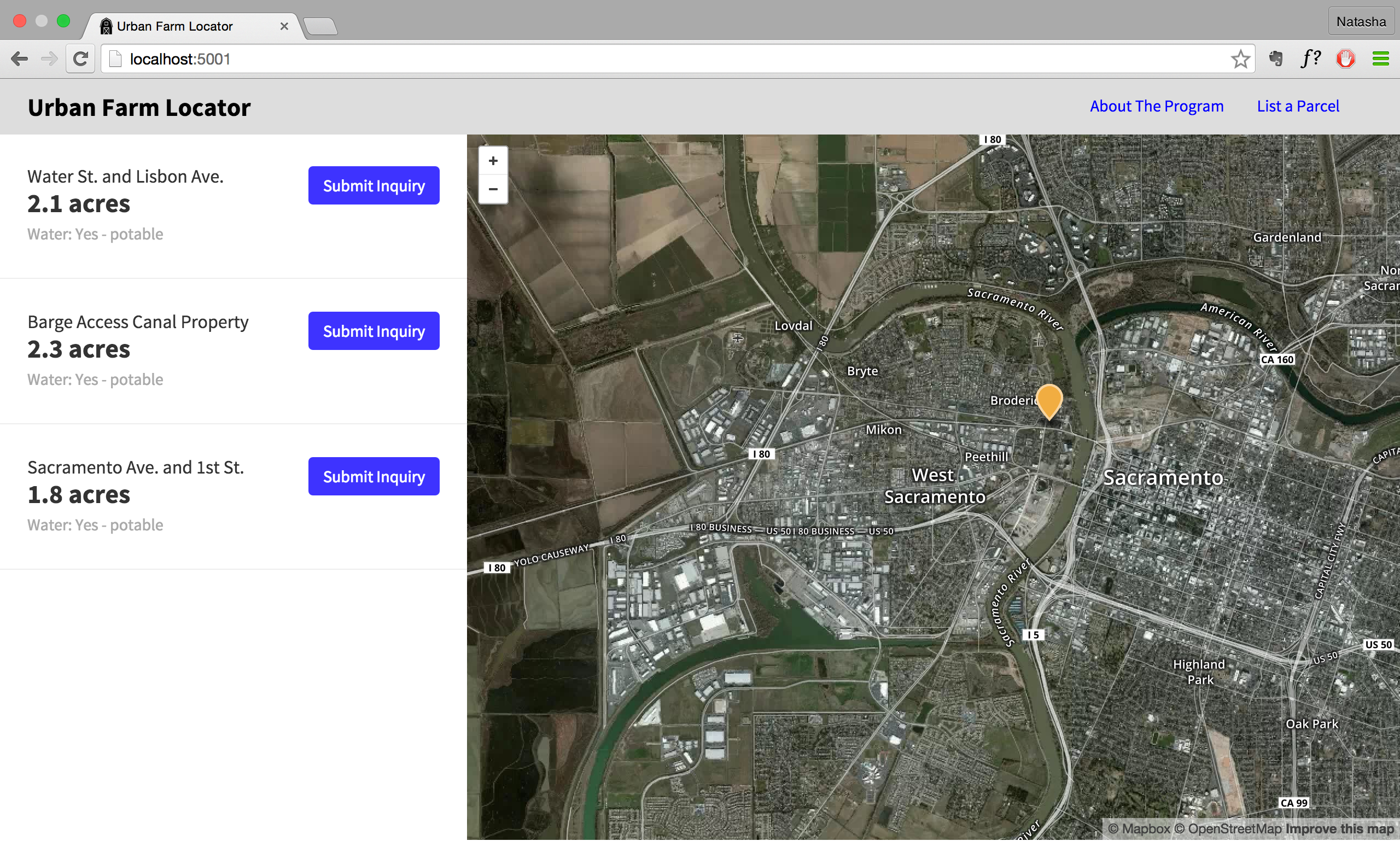

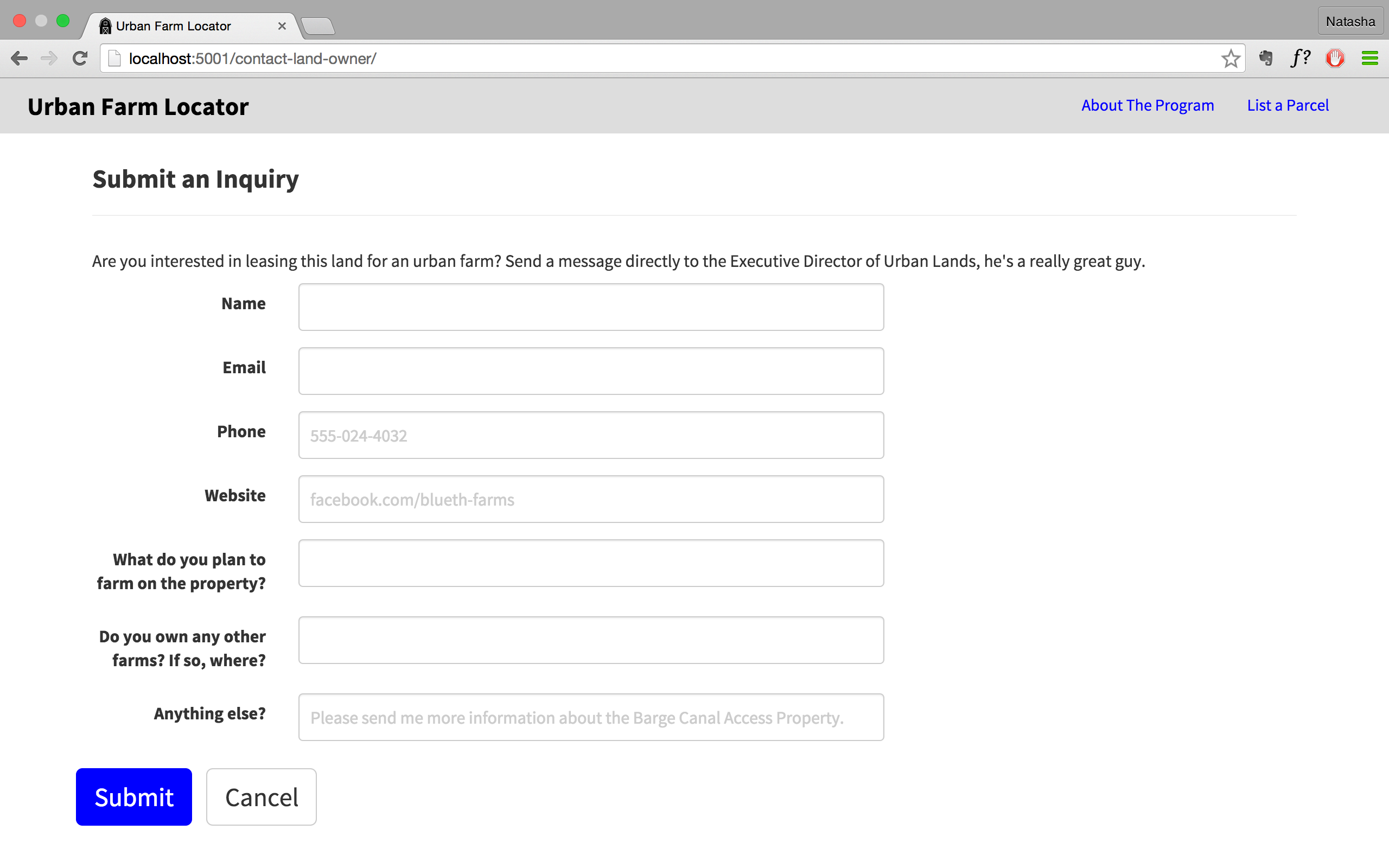

We spoke with farmers, residents, and community partners and learned how time-consuming it can be for aspiring farmers to find suitable farmland, so we created an Urban Land Locator that helps new farmers find and express interest in leasing vacant, under-utilized, farmable lots of land. By using technology that aggregates data about the soil and water availability of each parcel and shares in an effective way, we are streamlining a critical part of the process that helps farmers start urban farms.

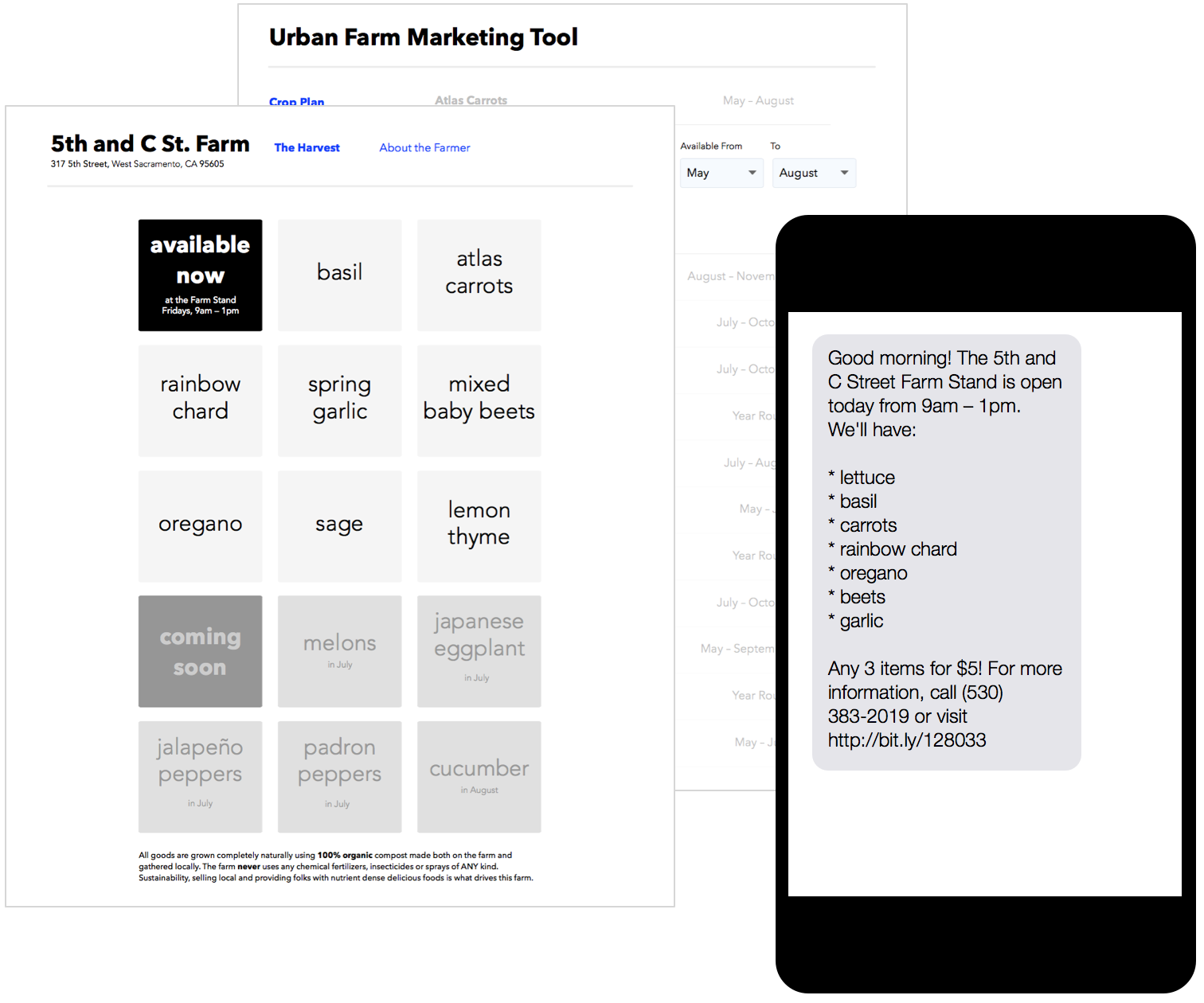

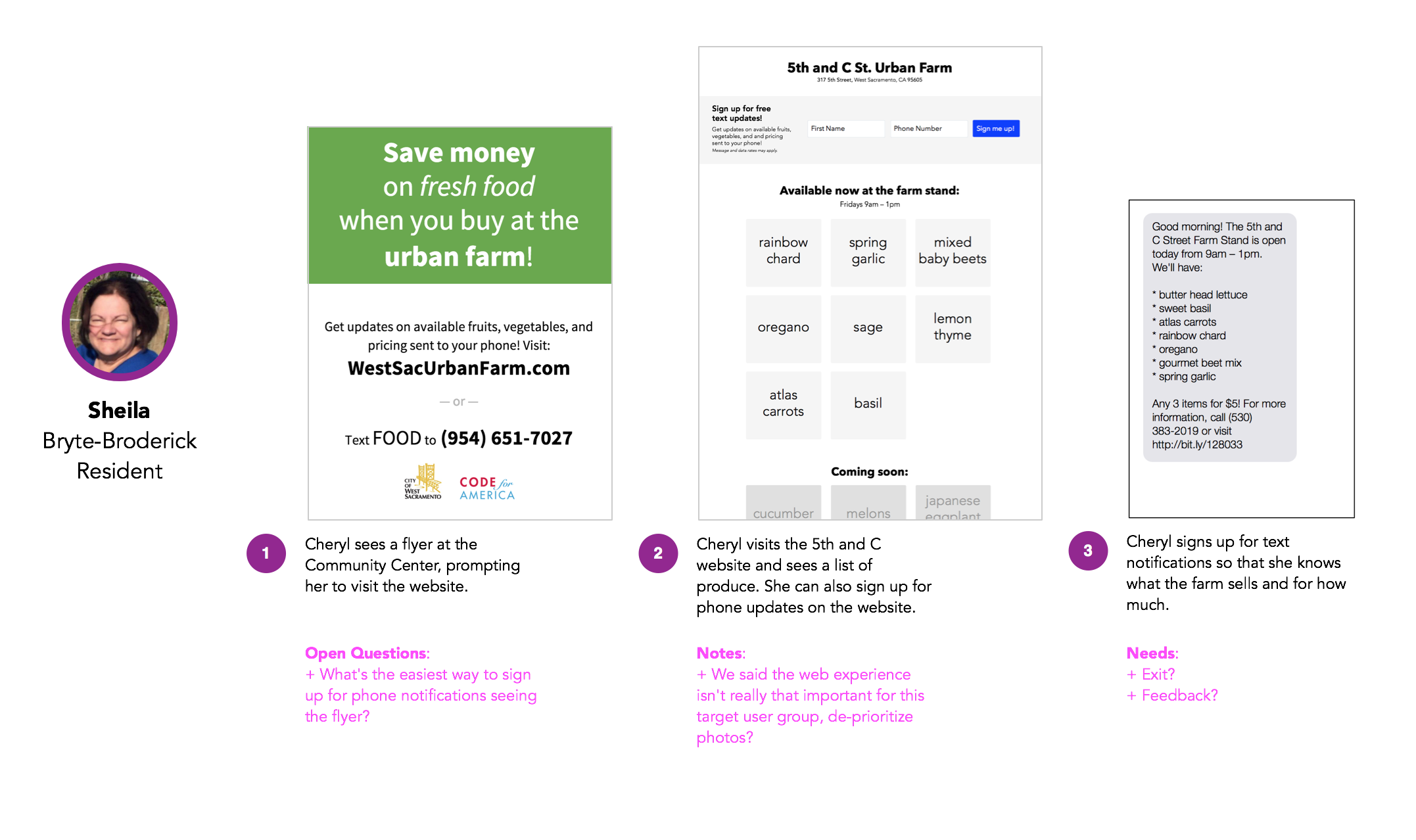

What about after those farms are in production? Our research found that many residents either aren't aware of the farms' existence, or don't understand how to purchase food from the farms. The farmers, in turn, have focused their efforts on selling to existing retailers, diluting some of the potential community benefits from localized sales. We're working on a Digital Farm Stand to improve awareness and help urban farms better reach West Sacramento residents. Residents will be able to see what farms are growing, what they plan to grow, and provide feedback through whichever communication channel they prefer.

Our Team

Fellows

- Natasha Fountain, Designer and Researcher, Code for America Fellow

- Grant Smith, Developer, Code for America Fellow

- Imanol Aranzadi, Designer and Developer, Code for America Fellow

City Partners

- Jon Robinson, Deputy City Manager, City of West Sacramento

- Raef Porter, Raef Porter, Climate and Energy Manager, Sacramento Area Council of Governments

- Martin Tuttle, City Manager, City of West Sacramento

Community Partners

Problem Statement

How might we support entrepreneurship in agriculture and food industries, and better connect people to the source of their food?

The goal of our project is to increase local awareness of, and consumption of food from, local farms and to make West Sacramento's urban farming success more easily replicable in other jurisdictions. Among other things, our project will help address food deserts by making it easier to start new urban farms, and enable local farmers to connect with their surrounding communities and promote the sale of farm-fresh produce directly to residents. Some additional benefits include repurposing blighted urban properties, increasing walkability of nearby communities and facilitating professional opportunities for aspiring farmers. Finally, our project will provide recipes and community education to help residents learn how to cook with region's locally grown produce.

City Context

In West Sacramento's urbanized areas, many privately-owned vacant lots are not properly maintained, creating visual blight that facilitates dumping and other unwanted activities while discouraging investment in the community. These lots generally exist in poorer areas of town that are also considered “food deserts” due to their lack of convenient access to grocery stores. Additionally, research has shown that residents walk less in a place for every vacant parcel and parking lot. The perception of a neighborhood's livability, walkability and public safety all increase with the addition of urban farms.

The City has embraced the urban farm movement as a means of transforming blighted properties, while generating economic activity and increasing the amount of healthy, locally-produced food available to West Sacramento residents. To facilitate the establishment of new urban farms, the City has worked with a local agricultural training organization, the Center for Land-Based Learning, to allow newly-trained farmers to lease unused City land for $1 per year and to defer water connection fees in order to establish working farms in urban areas. Together, this work improves career path opportunities for local farmers while greatly benefiting the local community and the City.

“The level of excitement and community support for the urban farming initiative has been extraordinary. West Sacramento residents recognize urban farms as an asset and are eager to have more sites like our flagship 5th and C farm in our town.”

—Mayor Christopher Cabaldon

The first urban farm in West Sacramento was built on a vacant lot in the Broderick neighborhood, and has produced 7,500 lbs. of produce in its first season. Several additional urban farms are expected to begin producing this summer as well. As these farms begin selling vegetables locally, the sites upon which they operate are transformed from weed-strewn eyesores to productive green spaces that enhance the community, generate economic activity and create new opportunities for residents to purchase locally-grown food right in their own neighborhoods.

“It improves the look of our community.”

—Cheryl, Bryte Resident

While West Sacramento's urban farm initiative has been quite successful in its early stages, there is room to build upon the program's community benefit, and its replicability in other jurisdictions.

Research

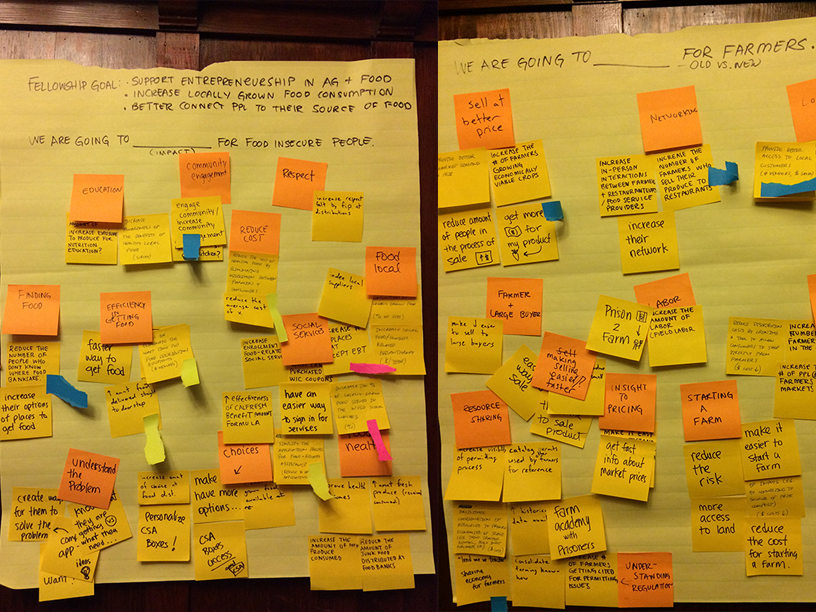

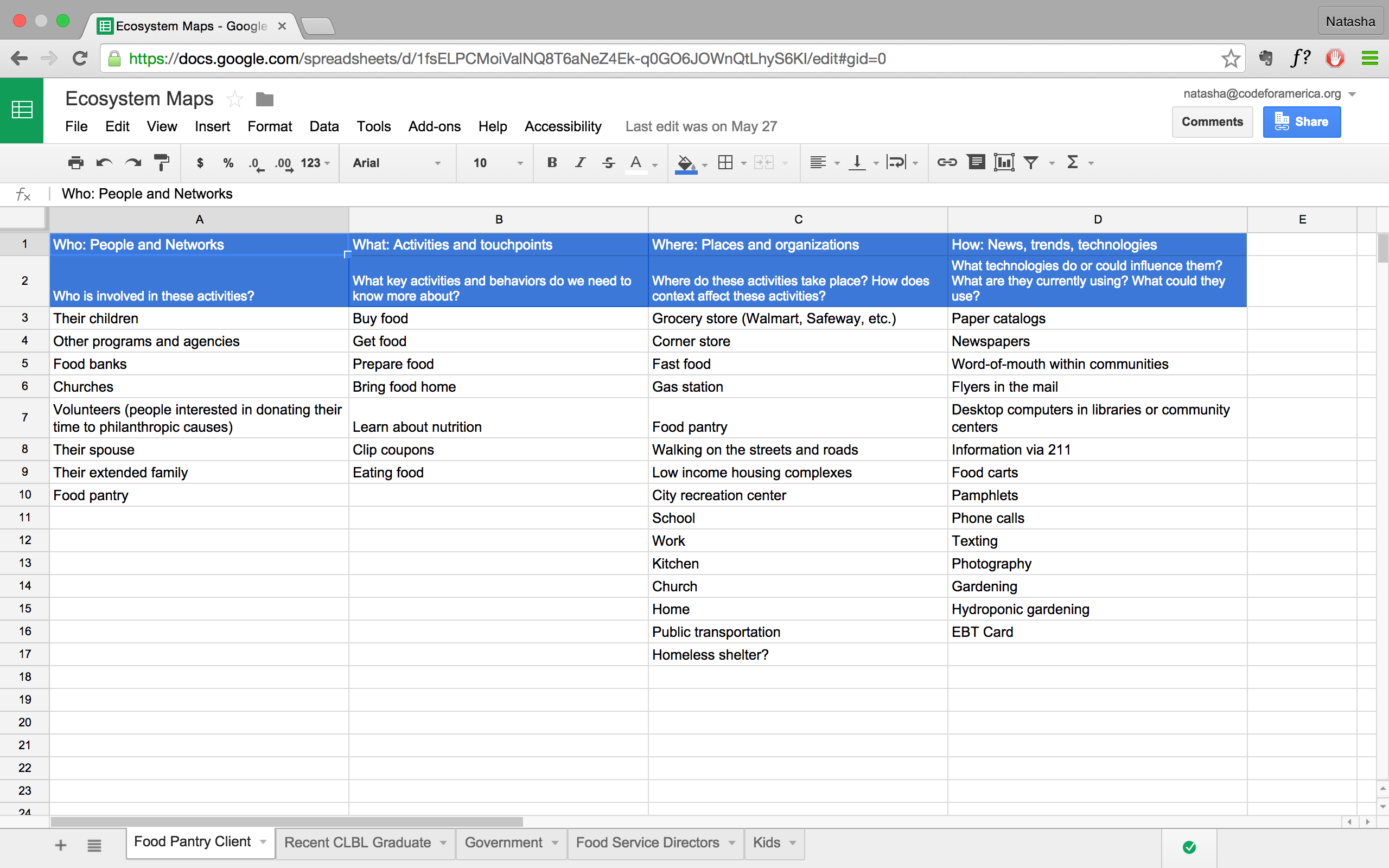

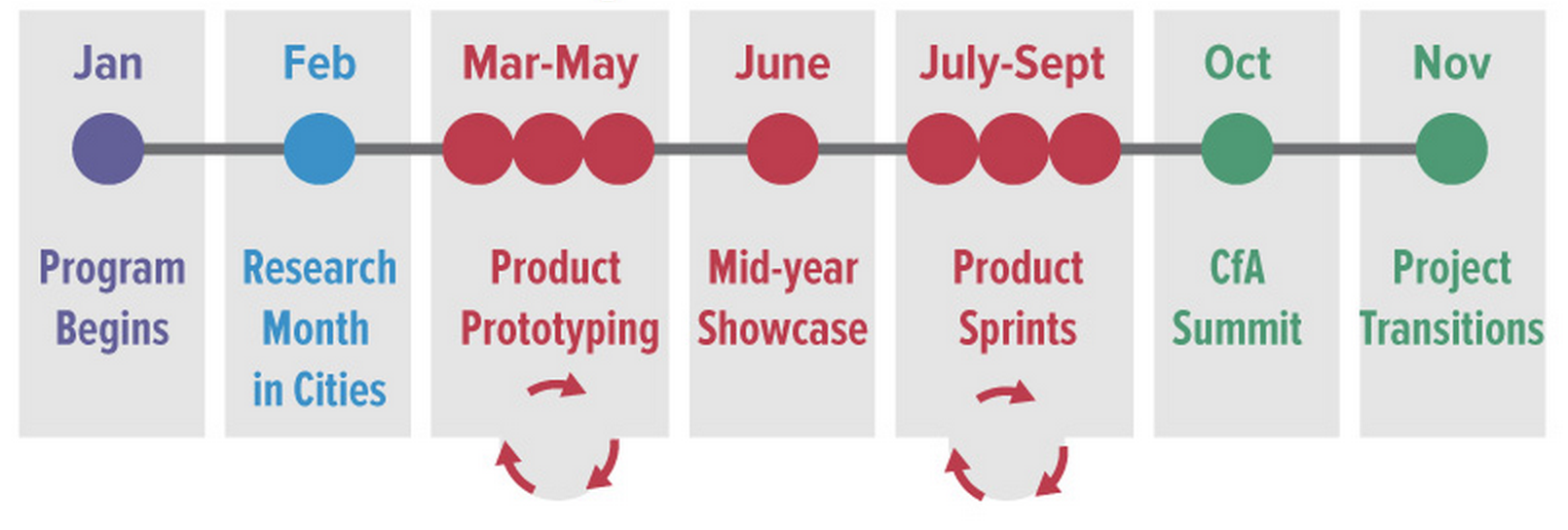

Like other fellowship teams, we spent February residing full-time in our partner city to understand the city's goals, engage stakeholders, and uncover opportunities for our project. We talked to residents, farmers, grocers, produce distributors, packing houses, institutional buyers, educators, county departments, community partners, and experts. The food ecosystem was huge and the research was broad.

Food Insecurity

By the end of February, we had volunteered at several food pantries and developed a basic understanding of some key needs, goals, and behavior of the food insecure in West Sacramento.

“To get my mom to change her diet, you'd have to give her free food.”

—SNAP recipient

- Affordability. "Improving access to affordable healthy food" is the #1 thing Americans believe would improve their health a great deal, according to Feeding America's 2014 Hunger in America.

- Convenience. While many organizations offer free food to the working poor in West Sacramento, the effectiveness of their services varies. Pantries operate during working hours, sometimes with long outdoor lines in intense heat or rain. We even saw families who walked to pantries refuse free, whole chicken because it was too heavy to carry home.

- Choice. Since food at pantries is donated from local food banks, families don't have much choice as to what they are given when they arrive. We heard over and over again that being able to have more say in the food would be amazing, and noticed that their experience was in sharp contrast to food services that emphasized door-to-door delivery, convenience and choice for wealthier populations.

Urban Farms

Throughout February, we also worked closely with the Center for Land-Based Learning, a community organization that partnered with the City of West Sacramento to train new farmers. Perspectives from partners and graduate farmers helped us understand needs of beginning urban farmers:

“Getting regular buyers is hard. Getting your product list out there is hard.”

—Sara Bernal, urban farmer

“The best available land is already owned by someone, but they have no plans for it.”

—Mary Kimball, Executive Director at Center for Land-Based Learning

- Access to land. New farmers coming out of the program would need land in order to establish their practice. The City of West Sacramento had been helping farmers find city-owned parcels, but the data wasn't particularly helpful and private owners weren't yet included in the conversation.

- Finding a market. Inventory and demand fluctuates so much per season, and market need is usually passed on anecdotally from distributors and restaurateurs down to farmers, but the information isn't quick enough.

Strategy

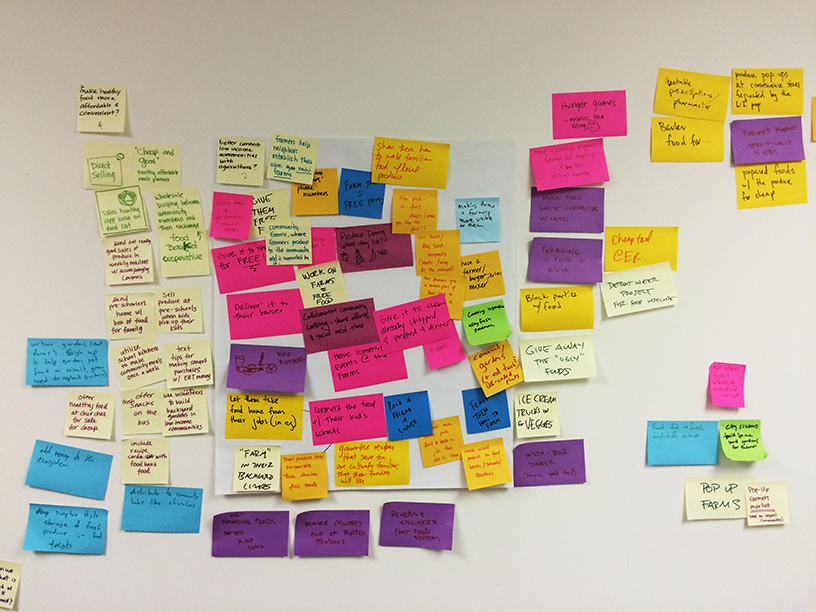

We decided to explore these distinct problem areas in tandem throughout March. As a team, we kept from defining the problem too narrowly too fast so that we'd be more open to possibilities as we explored potential solutions. We gave ourselves until the end of the month to execute a small pilot for each problem area to better understand which one we should focus on for the fellowship.

Prototypes

Affordable Produce Service

We wanted to directly address affordability, convenience, and choice, so we came up with a solution that would provide low-income residents with subscriptions to affordable local produce, delivered straight to their door each month.

For the prototype, we assembled a box of organic food:

- 1 bunch of bananas

- 1 head of lettuce

- 1 avocado

- 2 potatoes

- 2 apples

- 2 oranges

- 1 dozen eggs

We went to a local food pantry and tried to sell our box of food for $10. We explained our idea of a subscription model, and offered pantry visitors the opportunity to sign up for subscriptions to get more food, but no one would buy it. No one offered contact information to subscribe, either. Some reasons why:

- Perceived value. One guy looked at each item in the box, rattled off the price of the item at his local supermarket, and added them quickly in his head. He determined that for the price, the box wasn't a good deal, especially in the context of working around the free resources already available (like the pantry).

- Individual preferences. One size doesn't fit all, especially when it comes to food. Clients at the pantry had a range of preferences, disabilities and diet-related illnesses that made one or more items in the box undesirable to them.

- Cash. Some of the families didn't have cash to spare to buy food, but would purchase the box if they were able to use their SNAP benefits.

- Immediacy. Those who liked every item of food and felt the price was reasonable had trouble reconciling the idea of spending money on something they wouldn't get right away. As a way to conserve resources, people working on a tight budget tend to spend things only when they truly have need. For grocery purchases, this results in most cash expenditures occurring on specific, highly-desired items (hot prepared food is normally exempt from food stamp purchase) and on everything toward the end of the month.

The feedback we received about the box prompted questions on key aspects of the business model: Who could we really help? Who was willing to help us? Did our cost structure make any sense? After a meeting with a potential partner, we learned that the financial viability of the solution would be a stretch—the business wasn't willing to price the food as low as we'd expected, which would require a large portion of the costs to be subsidized in order to meet the price point for our target users. The economics just didn't work out.

We were also concerned about the mounting effort ahead. This project required less technical expertise and more community organizing and business effort—not necessarily our wheelhouse as developers, designers, and researchers. Even though we were up to the challenge of building a new service, given the timeline of our fellowship, we wanted a project that would give us the opportunity to explore a compelling digital product and allow each of us to shine doing what we do best.

Digital Farm Stand

Since partnering with local businesses and establishing a new food delivery service was too complex an effort for our timeline, we wondered if we could leverage food from the local urban farms. We returned to West Sacramento and did some quick interviews with residents and urban farmers to better understand how the urban farms were impacting the population we wanted to help.

We learned:

- Residents of West Sacramento really love their neighborhoods. Most people we spoke to had lived in the community for at least 15 years and took pride in their neighborhood and sense of community.

- People liked the idea of the urban farms, but didn't know much about what it actually produced or who ran it and why. “It improves the look of our community” was heard as much as “I didn't even know they sold food.”

- People were more knowledgeable about farming than we assumed, and many people we spoke with grew their food or found ways to get fresh food. The ones who farmed learned from family members and did it with varying degrees of success but they were interested and wanted to learn more.

It seemed clear that there was a disconnect between the urban farms and the residents of the community that they were supposed to be serving. Farmers didn't always know about residents' needs, and residents didn't understand how urban farms could easily meet some of their needs. We wondered: how might we deepen the impact of the urban farms and have the food better reach the people in the community?

We're working on a product that will better market urban farms to the people who need them most. It will enable residents to receive updates on cheap produce available and give feedback on food they want to see grown at the farm.

We're exploring which touchpoints will best reach residents. We've collected names and phone numbers of people who are interested, and discovered they were really excited about receiving information on “deals at the urban farm” (their words). Their language reiterates the importance of affordability and value for this population and gives us hints on branding that might work best.

Food Pantry Delivery Service

We've built a great relationship with some of the pantries in West Sacramento and have learned a lot about them and the families they serve. In line with our research findings from February, we wanted to explore how getting food at the pantry could be more convenient. What if we partnered with a ridesharing service to get food delivered from pantries to people's houses? What would the impact to the pantry be? How helpful would it be to families?

To find out, we collected names and addresses of 10 clients at a local pantry and offered to deliver their food to them for a couple of weeks. We rented a car and made the deliveries ourselves.

The impact to the pantry was minimal, but the volunteers weren't thrilled about potentially not interacting with anyone if all food was going to be delivered. The volunteers there liked helping out and feeling useful.

The families we delivered food to loved it, but just delivering to 10 families took around 2 hours. After the first day, it was clear this wasn't going to scale well and the impact was negligible. We didn't pursue it any further.

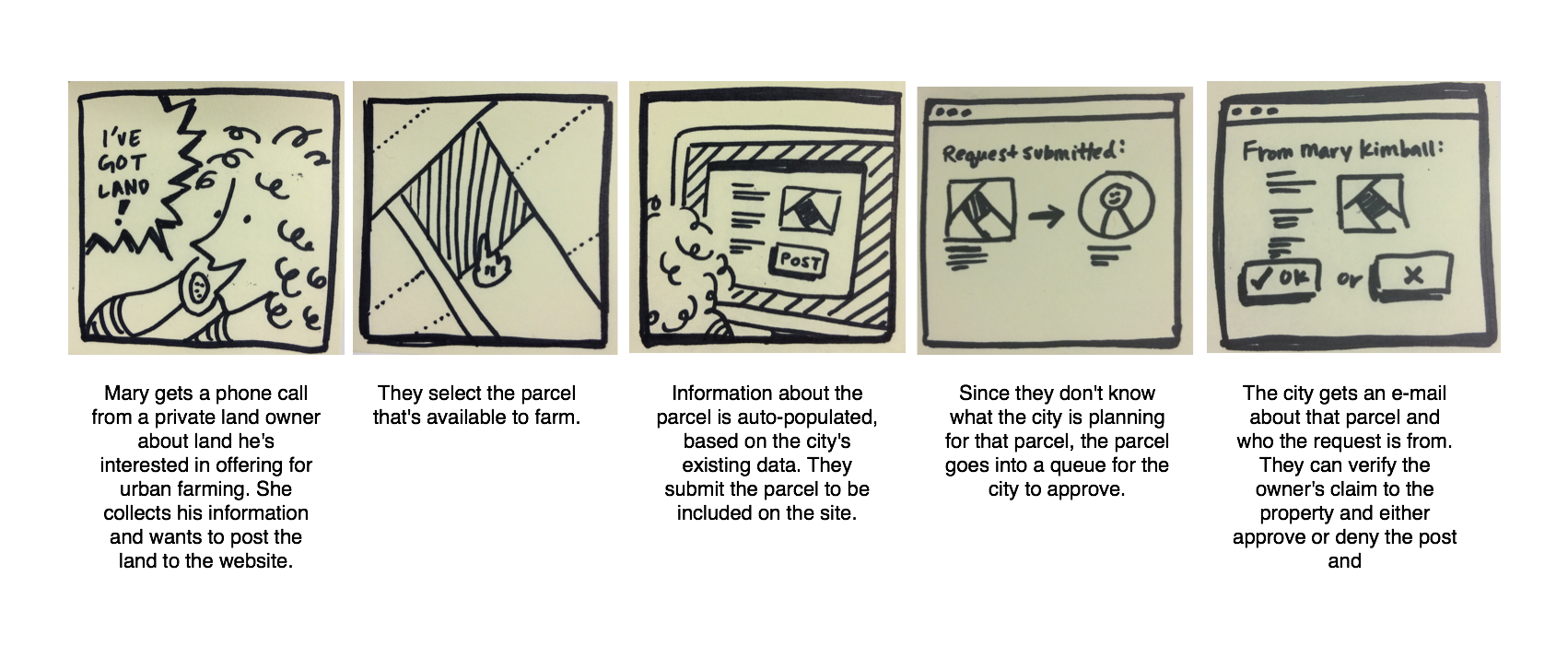

Urban Land Locator

From our first interviews with beginning farmers, we heard over and over again that land access was or had been an issue, so we began prototyping what a solution might look like from early March.

Since then, we've gotten feedback from the City, community partners at Center for Land-Based Learning, and beginning farmers. We're confident this solves a real problem for new farmers seeking urban land and we're still testing and iterating.

Based on their feedback, we've made several changes and are exploring new interactions, clearer language, and an improved information hierarchy.

Next Steps

The land locator already has a number of workflows that will need to be further implemented and fleshed out. These include posting land and browsing the available postings as well as contacting the appropriate city representative or private landowner. Additionally, we have a number of data sets from the City of West Sacramento and from SACOG that we want to include. These range from soil quality to water availability to whether or not the property is part of a food desert.

Digital farm stand will be a combination of tools for maintaining produce availability at an urban farm and sharing that information with local residents. From the farmers' standpoint, we aim to make the interaction of updates as simple as possible. Farmers will be able to edit information using a text messaging system, convenient for when you're out in the field with your feature phone. On the resident end of things, we will test a variety of methods to distribute the information about what's available at nearby urban farms: phone, text, email and flyers.

We are continually facing a couple more general, forward-focused questions: how will the tools and interaction changes be maintained, and specifically, which organization will take charge of these new technologies? Another important upcoming task is working with the City on the process of signing a lease for the land to understand how our technology can grow into this frame, so that the process of getting land will be faster and simpler, even after the farmer finds the land. And of course, we are always considering that the technology needs to be scalable and redeployable.

We envision a future West Sacramento where it's easy to establish urban farms, and where those farms can quickly connect with the communities that surround them in order to maximize the extent to which farmers and nearby residents alike share in the farms' bounty.

Further Cultivating Experiences

Events

For Code Across, we hung out at Hacker Lab in Sacramento with the folks at Code 4 Sac. Projects there ranged from improving awareness of third spaces in the region to creating tools to help locate food distributions. With over 70 attendees and 15 pitches, it was really great to see all the excitement around civic hacking in Sacramento and West Sacramento! And of course the food was great too :)

Tools and Processes

To stay focused and coordinated, we've been using waffle.io, a visualization and tracking tool that works on top of GitHub. We currently have two main repositories as well as a third 'meta'-repository that we use to combine all the repositories we are interested in at any given time.

We'd love for you to join us in our work, so feel free to reach out any time!